TL;DR (too long; didn’t read)

Some of the layers of the Obernkirchen Sandstone show countless footprints of different dinosaurs. Some 140 Ma ago, carnivorous and herbivorous dinosaurs lived in this area. Parts of the track-bearing layers are openly accessible and offer a brief view into the era of these ancient beasts.

Dinosaurs are an extremely successful group of terrestrial vertebrates and almost everyone has heard about the countless spectacular dinosaur fossils from Asia and South America. Furthermore, there are lots of fossils of these creatures known from several locations across Europe. One of these locations is the Bückeberg near Obernkirchen in Lower Saxony, Germany. Here, the dinosaurs literally left their traces…

It’s been a while…

During the Early Cretaceous, the world looked completely different: most parts of Europe were submerged and the continent resembled an archipelago. We know how old the dinosaur footprints at Obernkirchen are, because the sedimentary rocks in which they are preserved also contain the fossil ostracod Cypridea alta formosa. The occurrence of this animal dates back the tracks to 140 Ma before present.

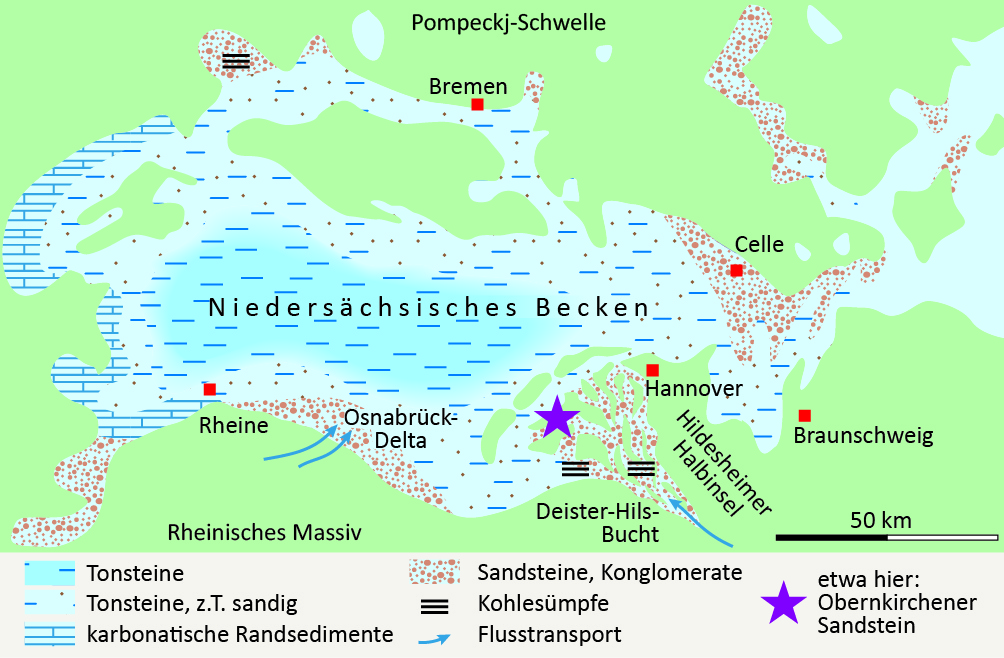

The landscape in which the dinosaurs left their tracks was a mixture of swamps, lagoons and river deltas. Additionally, a land barrier separated the area from the Lower Saxony Basin which was a vast water body, reaching from what is now the Netherlands to Braunschweig. Southerly, it was delimited by the Rhine Massif, which in turn gradually delivered the erosion products for the formation of the Obernkirchen Sandstones.

Ancient tracks in the quarry

The dinosaur tracks at the Obernkirchen Sandstone (a thin layer within the Bückeberg Formation) make an appearance at several locations in Lower Saxony. Most of them are not accessible anymore due to urbanisation, afforestation and mining. Yet, the sandstone layers that are still visible offer a view in a time long ago, when quadrupedal, heavily-armoured ankylosaurs and long-necked sauropods encountered bipedal herbivores and carnivores. Herein, we will have a closer look at the tracksites of a quarry, which is situated in the forest east of Obernkirchen. There are two-toed and three-toed footprints of small and big dinosaurs with different dietary preferences. Here, the Obernkirchen Sandstone has a thickness of about 8 meters. Track bearing layers are quite rare and thin. Additionally, they are not continuously at the whole area. This is caused by geological faults, but also due to mining activities. However, at least six layers, containing dinosaur tracks crop out.

The so-called “chicken yard” is the lowest known track layer and shows hundreds of tracks from herbivores and carnivores of different sizes. Some tracks that show only two instead of three toes are believed to be created by troodontids; these are small, feathered and carnivorous dinosaurs which held the second toe above the ground while walking. The famous Velociraptor is a close relative of Troodon. Occasionally, the troodontid tracks can be followed for several meters. The chicken yard is located in the centre of the active quarry and hence, not accessible for the public. For that reason, we are happy to present a 3D scan of this unique location.

In the layers above the chicken yard, the footprints of three-toed ornithopods can be found occasionally. Ornithopods are herbivores and some of them could grow up to ten meters and more in body length. One of the best-known representatives of this group is Iguanodon, which is also believed to be the creator of many tracks at the Obernkirchen Sandstone. Some small, irregular imprints may have been produced with their forelimbs. These small imprints show that some ornithopods walked on all fours from time to time.

Dinosaurs are not dead

Dinosaurs thrive since roughly 245 Ma and just like the extinct pterosaurs, modern crocodiles and birds they belong to the archosaurs. Since the onset of the early Jurassic 200 Ma ago, dinosaurs were the dominant terrestrial vertebrates in many ecosystems. Due to their overwhelming variety of shapes and sizes, they became icons for earth’s history and evolution. The biggest terrestrial animals that ever walked the earth are dinosaurs and on top of this, they never went extinct. Modern birds are – biologically considered – dinosaurs, and they survived the mass extinction 66 Ma ago. With at least 10.000 recent species, they are the species-richest group among terrestrial vertebrates. On the other hand, there are around 6.400 species of mammals nowadays – in a way, we are still living in the age of dinosaurs.

What tracks reveal

Usually, paleontologists work with bones and other hard parts of extinct organisms. Ichnofossils (fossilized tracks) are something very different. While an animal can only die once and leave only one skeleton during its lifetime, it is able to create countless footprints, resting traces, burrows and feeding traces. That’s why tracks directly reflect the behavior of a living creature; the track maker was alive at this very moment when it left these ancient marks in the sand or mud. Due to all this, the ichnology requires a completely different approach for research. For example: anatomically, the feet of most theropods (carnivorous dinosaurs) are pretty similar to each other and hence, different species are able to leave almost identical tracks. On the other hand, one individual can produce different tracks by variation of the pressure, spreading of the toes, and alike. And of course, the property of the ground the animal is walking on has a high impact as well. All this makes it hard to exactly identify the track maker, and often we are only able to determine a certain group of animals as suitable suspects. Still, since we know the body plan of many dinosaurs, we can gather a lot of information: e.g., the speed of an animal – did it run or was it just strolling? Did it have any anomalies that had an influence on its locomotion? Additionally, we can even estimate the body length.

The animals that walked right here 140 Ma ago, were looking for food or conspecifics, just like modern animals. Some might fled from dangers. They were breathing, eating creatures and might have suffered from injuries or sickness. The tracks of the Obernkirchen Sandstone offer a short view into their lives. Their evolution continues into our present and even if we are not aware of it, their history is part of our everyday life.

Obernkirchen sandstone famous as natural building stone

Selection of buildings that used the Obernkirchen sandstone for construction. (see Obernkirchener Sandstein AG Broschüre (1913) and https://www.obernkirchener-sandstein.de/en/referenzen)

The Obernkirchen sandstone is composed of 95% fine-grained, uniform and therefore densely packed quartz grains, which are predominantly siliceously cemented. According to the texture, the rock is so thick-banked that large workpieces can be produced in blocks. The lack of stratification within the beds is advantageous. On the one hand, sandstone is hard and resistant, but on the other hand, it is easy for stonemasons to work with, which makes it a very popular natural building stone that has been quarried since the 11th century. Many castles, churches, council and patrician houses in northern German and Dutch cities were built of Obernkirchener sandstone, especially during the Weser Renaissance. The sandstone was transported via the Weser to Bremen, where it became a product of the Hanseatic League and was exported as “Bremer Stein” by Bremen merchants to all of Europe and the USA. The Hanseatic city, where a flourishing stonemason’s guild developed in the Middle Ages due to the Obernkirchen sandstone, possessed the stacking right for the sandstone and thus a long-distance trade monopoly. Only the stonemasons of Bremen were allowed to process the raw stone cut in Obernkirchen. Even today, the natural building stone is very popular and is quarried by Wesling Obernkirchner Sandstein GmbH & Co. KG, processed in production facilities in Obernkirchen and marketed.

Impressions

3D models

Due to technical difficulties, the high resolution model will be online in the upcoming weeks.

References

Hornung, J. J., Böhme, A., van der Lubbe, T., Reich, M., & Richter, A. (2012): Vertebrate tracksites in the Obernkirchen Sandstone (late Berriasian, Early Cretaceous) of northwest Germany—their stratigraphical, palaeogeographical, palaeoecological, and historical context. Paläontologische Zeitschrift, 86(3), 231-267.

Maik Raddatz-Antusch, M. (2019): Die Sandsteine des Bückebergs bei Obernkirchen. Naturhistorica, 161.

Meschede, M., & Warr, L. N. (2019). The geology of Germany: a process-oriented approach. Springer.

Nesbitt, S. J., Desojo, J. B., & Irmis, R. B. (2013). Anatomy, phylogeny and palaeobiology of early archosaurs and their kin. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 379(1), 1-7.

—In friendly cooperation with Wesling Obernkirchener Sandstein GmbH und Co. KG. —