TL;DR (too long; didn’t read)

Along with the UNESCO World Heritage site “Grube Messel” near Darmstadt, the fossil site “Korbacher Spalte” (Korbach fissure) is the most important paleontological site in Hesse and our newest geosite of the 30 Geotope³-series. The findings of Europe’s oldest fossil-bearing fissure filling mark the initial evolutionary phase of mammalian development in the Permian geological era. The fissure in the limestone was created around 255 million years ago in Late Permian (Zechstein) by an earthquake and was uncovered in 1964.

History of discovery

The discovery of the “Korbach fissure” was made possible by limestone quarrying at the southern edge of the district and Hanseatic town of Korbach (Waldeck-Frankenberg district), which lasted until the 1970s. In the now-closed “Fisseler” quarry, the state geologist Dr Jens Kulick discovered the fissure in 1964 during a survey of the area when producing the geological map of Korbach (GK25). The fissure was found in a section of the western quarry wall and was filled with clayey siltstone containing numerous fossil bone remains. Dr Kulick described bone fragments up to five centimeters in size and initially determined the findings to be of the glacial Middle or Old Pleistocene age (Kulick, 1968). One of the findings, a lower jaw fragment with well-preserved teeth, after improved conservation and preparation, could be assigned to the Upper Permian genus Procynosuchus by the Institute of Geosciences at the Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz. This was a reptile with mammalian characteristics that was previously only known from African sites (Sues & Boy, 1988).

Since its discovery, building deposits and rubble have endangered the Korbach site. As a result, the Hessian Ministry of the Environment announced in June 1991 that the Hessian State Office for Soil Research (now the Hessian State Office for Nature Conservation, Environment and Geology) would create a “comprehensive protection concept”. It considered the importance of the Korbach discovery was “just as great as that of the findings from Messel and Solnhofen (Bavaria)”. The first research excavation of the fissure took place in July 1991 under the direction of Dr Eberhard Frey (Natural History Museum Karlsruhe) and Prof. Dr Hans-Dieter Sues (Smithsonian Institution/ National Museum of Natural History in Washington/ USA). The excavation had technical support from Wolfgang Munk (Karlsruhe) and a local specialist for Zechstein fossils, Hartmut Kaufmann. It was also financially supported by the National Geographic Society (Washington). According to the excavation report, at least seven different tetrapod taxa were detected following initial evaluations and at least five were unknown to the Upper Permian of the northern hemisphere. “The fauna has been linked to the important tetrapod assemblages of the Upper Permian as part of the Karoo supergroup in southern and eastern Africa and therefore provides excellent correlation opportunities worldwide.”

Brief description and importance of the site

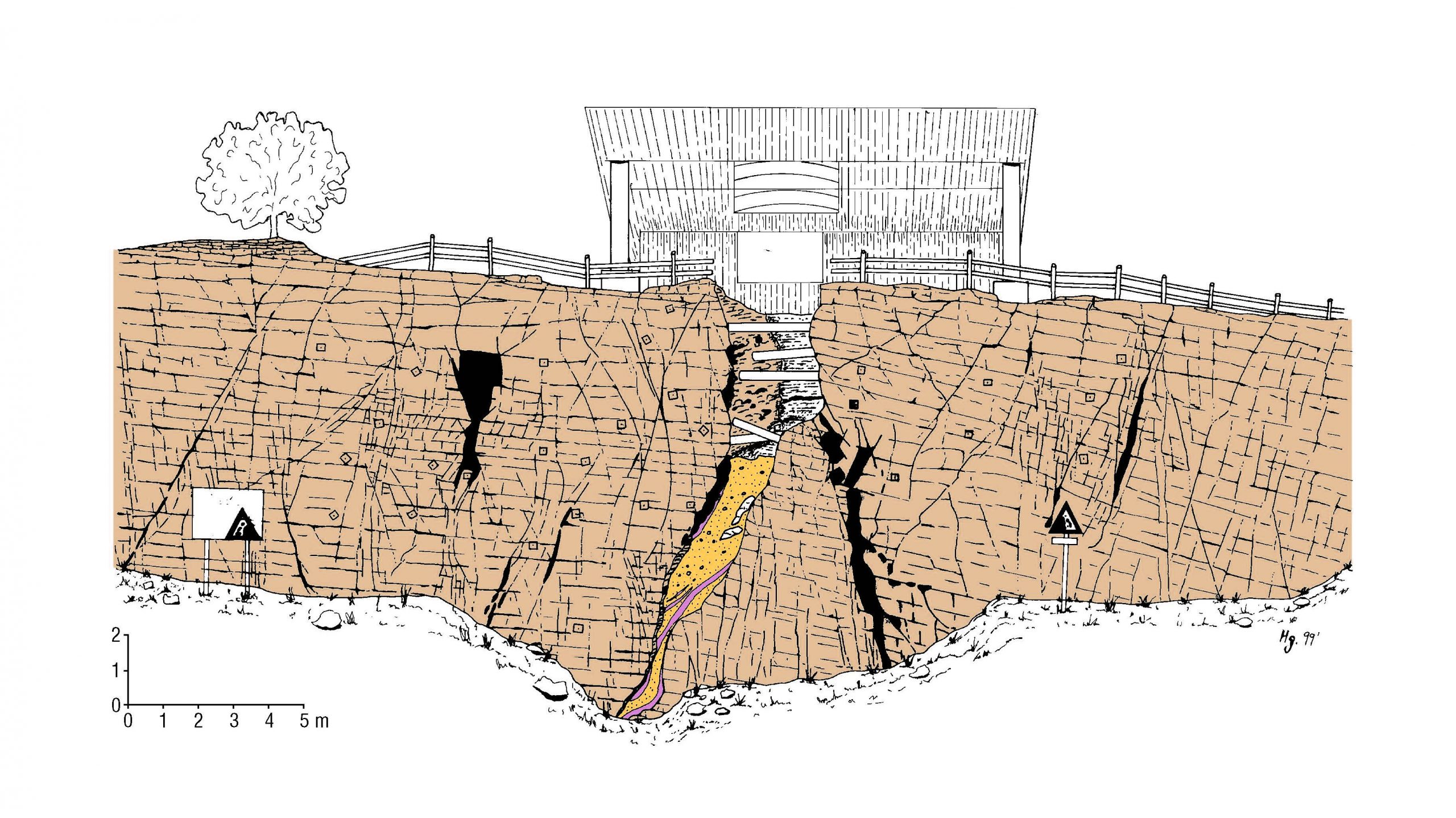

The fissure in the abandoned limestone quarry along the Frankenberger Landstraße in Korbach (see also Panek, 1994, 2012; Heggemann & Keller, 2003; Bökenschmidt, 2006) is approx. 12 meters deep with a maximum width of 3.8 meters. It occurs in a Permian aged limestone deposited as a marginal carbonate in the former Zechstein Sea. The upper part of the fissure shows signs of karstification. The deeper part is filled with yellowish to violet-colored sediment. The geological relationships in the quarry indicate that the fissure was formed around 255 million years ago by a tectonic event (with associated earthquakes). The structure continues over a length of at least one kilometer in the westerly or south-eastern direction. The fissure in the western quarry wall was almost completely uncovered by rock excavation in the quarry to reveal a cross-section of the structure but only a portion of the fissure-filling material was exposed. Investigations have shown that in the vicinity of Korbach there are other smaller, fossil-bearing fissure systems in the same marginal carbonate. These contributed significantly to the interpretation of the genesis of the fossil sites and their dating (Becker et al., 1999; Bökenschmidt et al., 1999; Zeeh et al., 2000). A research borehole drilled in June 1999 by the Hessian State Office for Soil Research about 200 m west of the “Korbach fissure” revealed an approx. 30 cm thick weathered horizon of yellowish sediment at a depth of 35 m directly above the marginal carbonate. This horizon resembles the fissure filling in appearance and composition and is considered to represent the depositional horizon of the land surface at that time (Bökenschmidt et al., 1999; Bökenschmidt, 2006). Hence, the fissure itself as well as its sediment filling containing bone fragments formed after the first regression phase of the Zechstein Sea, i.e. after completion of the marginal carbonate sedimentation and when the limestones upper surface formed the land surface. Based on these relationships, the age of the fissure and subsequent infillings is considered to have formed during the Zechstein time between 257.5 and 252.5 million years (Paul et al., 2016). The finding of a Procynosuchus mandible (a genus of a mammal-like reptile) at the site was the first and only fossil of this type found north of the equator and therefore gave the location worldwide importance (Sues & Boy, 1988). The Korbach finding correlates with other Procynosuchus findings in South Africa (Beaufort Group), Zambia (Madumabisa Mudstone Formation), where an almost completely preserved skeleton was found, and Tanzania (Usili Formation). The locations of the reptile genus all represent sub-regions of the then global supercontinent of “Pangaea”. The first excavation in 1991 already confirmed that the Korbach fauna was made up of a large number of other tetrapod forms that represent different evolutionary stages of development or different lineages leading to today’s mammals, crocodiles, dinosaurs and birds. Findings of this type had previously been uncommon and widely scattered in the sedimentary rocks of the Kupferschiefer in Europe. Numerous other bone fragments of tetrapods were obtained between 2011-2015, as part of the cooperation project “Promotion of research and management of findings of fossil material from the Korbach fissure” between the district town of Korbach, the Wolfgang Bonhage Museum, the National Geopark Grenz Welten, the Natural History Museum of Kassel (Hessen), the Hessian State Office for Environment and Geology, the State Museum of Natural History in Karlsruhe and the Senckenberg Society for Natural History. These unique findings were described for the first time in Germany (Witzmann et al., 2019).

3D model

Impressions

References

Becker, F., Zeeh, St. & Heggemann, H. (1999): Isotopengeochemische Untersuchungen an Zechsteinkarbonaten der Fossillagerstätte Korbacher Spalte (NW-Hessen) als Beitrag zur Klärung ihrer Entstehung.- In: Hoppe, A. & Abel, H. (Hg.): Geotope – lesbare Archive der Erdgeschichte, Kurzfassungen der Vorträge und Poster zur 151. Hauptversammlung der Dt. Geol. Ges., Schriftenreihe Dt. Geol. Ges. 7:25; Hannover.

Bökenschmidt, S., Braun, A., Heggemann, H. & Zankl, H. (1999): Oberpermische Spaltensedimente bei Dorfitter südlich von Korbach und ihre Beziehungen zur Fossillagerstätte Korbacher Spalte, Geolog. Jb. Hessen 127: 19 – 31.

Bökenschmidt, S. (2006): Die Fossillagerstätte Korbacher Spalte – ihre Entstehung und Einordnung in den Zechstein Nord-Hessens, Dissertation am Institut f. Geologie u. Paläontologie/ Philipps-Universität Marburg/ http://archiv.ub.uni-marburg.de/diss/z2007/0090/.

Heggemann, H. & Keller, T. (2003): Die Korbacher Spalte – Eine einzigartige Fundstelle landlebender Saurier des späten Erdaltertums im Landkreis Waldeck-Frankenberg, Paläont. Denkmalpfl. Hessen 15, Wiesbaden.

Kulick, J. (1968): Erläuterungen zur Geologischen Karte von Hessen 1 : 25.00 Blatt Nr. 4719 Korbach, Hess. Landesamt f. Bodenforschung, Wiesbaden.

Panek, N. (1994): Wertvolle Fundstätte vor dem Verfall, Kosmos 9: 64 – 65.

Panek, N. (2012): Die „Korbacher Spalte“ – ein paläontologisches Welterbe im Zentrum des Nationaler Geoparks „GrenzWelten“, Jahrbuch Naturschutz in Hessen 14: 125 – 131.

Sues, H.-D. & Boy, J. A. (1988): A procynosuchid cynodont from Central Europe, Nature 331: 523 – 524.

Paul, J., Heggemann, H., Dittrich, D., Hug-Diegel, N., Huckriede, H., Nitsch, E. & AG Zechstein der SKPT/DSK (2018): Erläuterungen zur Stratigraphischen Tabelle von Deutschland 2016: Die Zechstein-Gruppe [Comments to the Stratigraphic Chart of Germany 2016: the Zechstein Group] .– z. Dt. Ges. Geowiss. 169 (2) p. 139–145; Berlin.

Witzmann, F., Sues, H.-D., Kammerer, C. & Fröbisch, J. (2019): A new bystrowianid from the late Permian of Germany. First record of Permian chroniosuchian (Tetrapoda) outside Russia and China, Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology/DOI: 10.1080/02724634.2019.1667366.

Zeeh, S., Becker, F., Heggemann, H. (2000): Dedolomitization by meteoric fluids: The Korbach fissure of the Hessian Zechstein Basin (Germany).- Journal of Geochemical Exploration, 69-70:173-176; Amsterdam.